Reliable DS Concept Review

1. Theorems

1.1 ACID

- Atomicity

Either the operation is performed by all of the replicas or by none of them

- Consistency (=> Data Consistency)

After each operation, all replicas reach the same state and send out the same output message (if needed)

- Isolation

No operation can see the data from another operation

- Durability

Once an operation completes across all replicas, its changes to data should survive crashes of replicas

Pros (theory)

Strong consistency at all times

Replicas are exactly substitutable for each other (exact redundancy)

No data is lost, no operation is lost

Rigorous consensus protocols to provide guarantees

Works in any distributed system, even without a global clock

Pessimistic: Accounts for the worst-case situation

Cons (practicality)

Complex protocols

Availability is less important than consistency

Scalability can be a challenge if everyone has to agree

No ways to handle consistency outside the crash fault-model

Pessimistic: Worst-case situation is rare, what about average-case?

1.2 BASE

- Basically Available

Tolerate partial system failures (if occurs, simply reboot these failed replicas)

High perceived responsiveness

Fast response

- Soft-state (or scalable)

Keep first-tier system not stroing any permanent data (if needed, keep it in ACID service elsewhere, or keep enough copies to make the potential partial failures doesn’t impact it)

If first-tier replicas dies, simply restart them from predetermined clean state

Use events to publish to every replica when state becomes consistent if needed

- Eventually Consistent

Use cached data to provide responses quickly, if possible

No need to always check for stale or inconsistent data

Skip blocking or skip locks on data

Respond now (surely), reconcile later (maybe)

1.3 CAP

Consistency, Availability, Tolerance to Network Partition

Network Partition (split-brain): A fault where the network splits into multiple disconnected portions, and where processors and processes in different partitions cannot communicate with each other.

Consistency: All clients see the same view of a data object, even as reads and writes happen to data objects

Availability: Every query returns a response, and all clients can find some replica to retrieve the data object from, even if faults happen

Partition-tolerance: System continues to operate despite different parts of the system becoming disconnected from each other due to network partitions

can not always achieve all at the same time

Trade-offs:

- prefer CA

All nodes must be in contact with each other at all times

You get consistent replication and availability

E.g LDAP, xFS file systems

- prefer CP

Some (minority or secondary) partitions are allowed to be killed off Some replicas are unreachable (but primary is good)

Systems where failed replicas are allowed to exist without possible hope of recovery

E.g. Distributed databases, majority-voting protocols

Question: If a network-partitioning fault creates 5 partitions, and we choose CP in the CAP theorem, how many partitions are running after the fault?

Answer: 1.

- prefer AP

You can get a response, but it might not be the right response

Systems where you might need to have leases on objects and expire them

E.g. DNS, Web caches

Question: If a network-partitioning fault creates 5 partitions, and we choose AP in the CAP theorem, how many partitions are running after the fault?

Answer: 5.

1.4 PACELC

Under a network partition (P) in a distributed computer system, trade-off availability (A) and consistency (C), else (E) when the system is running normally and partition-free, trade-off between latency (L) and consistency (C)

Proposes tradeoffs even under no-partition conditions

When high availability is wanted, we must have replications, then need to worry about latency to keep replicas consistent

2. Misc Concepts

Availability

Availability = Uptime / (Uptime + Downtime)

Fault -> Error -> Failure

Fault: Hypothesized case of error; have 2 states: dormant or active (when it produces an error)

Error: Incorrect system state, may lead to failure

Failure: System fails to deliver service

Failure are always not independent.

Fault Types

a. Fail-silent Fault (Fail-stop Fault)

The fault occurs in a single machine or component within the distributed system.

The faulty machine stops working and does not produce any outputs, erroneous or otherwise.

The fault does not cause other machines in the system to fail or behave incorrectly.

b. Latent Fault

will not manifest into an error

Consensus

Agreement reached by a set of processes, objects or processors about the state of the system.

FLP (Fischer-Lynch-Patterson) Theorem

Consensus is impossible in the face of a fault.

Classical Impossibility Theorem

It is impossible to detect if a server is slow or whether it has failed.

Applies only to distributed asynchronous systems.

Heartbeat

A pinging-style mechanism by which a process, processor or an object is detected to be alive and functional.

Idempotent operation

When doing an operation (e.g., processing an incoming request) repeatedly does not change the state of a replica.

Independent-failures assumption

The assumption under which replication works, i.e., that replicas fail independently of each other.

Boardcast & Multicast

Boardcast: send same message at the same time to all machines in the same network

Multicast: send same message at the same time to designated machines in the same network

Quiescence

A condition where a replica pauses, stops updating its state, stops processing any incoming application requests, and instead is involved in checkpointing.

Synchronous and Asynchronous System

Synchronous system using the same clock (the global clock), which provide ordering ways, synchronization evaluation, faulty detection, and so on. (fault detection using the global clock)

Asynchronous system machines have their own clocks. They do their job at their own pace. Messages are not required to arrive or handled at the exactly same time but with a flexible time bound. (fault detection using heartbeats and timesouts)

Virtual synchrony

Achieving logical “points” of consensus across different processors in an asynchronous distributed system, so that processors appear to see the same thing at the same “logical” time, despite the processors running on different clocks and working at different speeds with no global clock.

Strategies used after fault is healed

BASE: Fulfillment operations, or compensating transactions.

preference of AP in CAP theorem: Fulfillment operations, or compensating transactions.

preference of CP in CAP theorem: Restart killed partitions.

preference of CA in CAP theorem: None. It’s not partition-tolerant to begin with.

How to achieve dependability?

- Fault prevention

Good design of system

- Fault detection

E.g. heartbeat

- Fault tolerance

Error detection, recovery, logging, checkpointing

- Fault containment or removal

Corrective & preventive maintenance

- Fault diagnosis

Monitoring, root-cause analysis

- Fault forecasting

Simulation, modeling, prediction from process metrics (data from models)

Historical data, accelerated life testing, etc. (data from real systems)

Shades of Consistency

a. Strict consistency

State updates propagated instantaneously

Unrealistic, impractical

Not very scalable, blocking, quiescence, consensus, total order, no propagation delay, no latencies needed

b. Linearizable consistency

State updates appear to occur instantaneously at some point in time (using a global clock)

Used for the formal verification of concurrent programs, real-time systems

Not very scalable — global-clock requirement (total order)

No blocking, no quiescence, no consensus requirements

c. Sequential consistency

State updates occur in the same (total) order everywhere (without a global clock)

Order of state updates from the same client is preserved

Order of updates from different clients may not be preserved

Not very scalable — blocking, quiescence, consensus, total order needed

Used in ACID virtual synchrony model

d. Eventually consistency

Under quiescence (when all state stops updating), eventually, all replicas will converge to the identical state

Scalable — no blocking, no quiescence (except for event-publish), no ordering requirement

Used in BASE model

Determinism

The property of a process, processor or object, whereby the processing of the same message on a state variable produces reproducible, identical results.

A deterministic server means that its replicas produce the same set of responses and undergo the same state changes, when they are sent the same set of requests in the same order.

Nondeterminism examples

Multithreading, local timers, getimeofday(), local host-specific functions, local memory, local files — only if they affect server state or the reply from a server.

3. Building Reliable DS Strategies

3.1 Design Structure

3.2 Run-time

3.2.1 Replication

Making copies, keep copies as copies. If one copy fails, another copy does the work.

Related Concepts

- Consensus

A way to get a set of distributed processors/machines/replicas to agree on a common value

- Total ordering

All replicas receive same set of messages in the same order

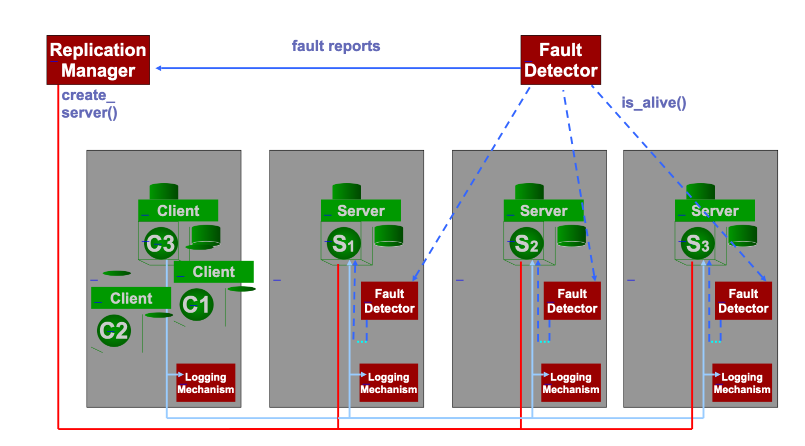

- Fault detection

Have a way of detecting when replicas die or hang. E.g. Local Fault Detector, Global Fault Detector

- Membership

Recording replicas that are correct and up-to-date replicas of the server

- Checkpointing

Have a way of giving newborn replicas the correct state

Need quiescence to avoid inconsistency

- Duplicate detection

Have a way of ensuring replicas do not perform duplicate operations multiple times

Needed in all servers. (needed for active server to detect duplicate client messages; needed for passive servers to detect duplicate checkpoint messages)

- Logging

Needed in quiescence, and in all servers.

Properties

Consensus needed

Never lose data

- Data must be preserved even if there is a fault

Never lose processing

- Retry operations in the event of a fault

Strong replica consistency

Replicas must be identical in state at all times

Typically no N-version redundancy and no voting mechanisms

Consistency even under nondeterminism (or assume deterministic behavior)

Consistency under ongoing operations, replicas crashing,replicas recovering, checkpoints occurring, etc.

Typical system model

Fault model: Crash-fault model with fail-silent faults

System model: Distributed asynchronous system (no global clock)

Active Replication (a.k.a. State-machine Replication)

All servers are active, receiving and processing all messages.

Active replication mandates determinism.

Improve recovery time by keeping small size of checkpoints. (less computing resources needed)

Components:

Checkpointing (to recover new replicas),

total order of messages,

logging (needed during replica recovery, during the checkpoint),

quiescence (don’t want the replicas updating their states in the middle of taking a checkpoint),

duplicate detection and suppression,

fault detection (to detect failed replicas)

Pros & Cons

Better in: recovery time, fault masking

Wrose in: resource usage

Passive Replication

Only one server is active (named primary), receiving and processing all messages.

Other servers (named backup) are passive, receiving state updates from primary.

Passive replication could be nondeterminism in some cases. (override the backup replicas’ states via checkpoints)

Improve recovery time by increasing checkpointing frequency.

Logs record the total ordering, duplicate detection, checkpointing, quiescence, and membership changing, but not fault detection because it is done by heartbeating which is independent to the system normal operating.

Adopted by Amazon EC2 EBS clusters. (with a single points of failure of control plane)

Components:

Periodic checkpointing,

total order of messages,

logging,

quiescence (needed during taking checkpoints from primary to backups),

duplicate detection and suppression,

fault detection

cold passive replication

The backup server (replica) is not actively running the application or keeping its state updated in real-time with the primary server.

Better in: saving computational resources

warm passive replication

The backup server is running and possibly receiving updates of the system state from the primary server frequently.

3.2.2 Recovery

Return system to its state before the error occurred.

Roll-back

Return system to its state before the error occurred.

Atomic commit needed (E.g. in Database)

Undo partial results to restore to clean system state.

Duplicate detection no needed.

Roll-forward

Move the system forward into an error-free state.

Retry to obtain error free result.

Proceed on and let error flush itself out of system.

Replication where a backup takes over after the working replica fails.

Duplicate detection needed. (because the non duplicate message is still needed to be proecessed, but at a future normal state, we will make a checkpoint of that state and forward it to other replicas)

3.3 Upgrading

Consistent replication is not the goal because the old and new replica are dissimilar pieces of software. Rather, continuity of operation (availability) is the goal.

3.3.1 Big Bang

upgrade is done at once, across the entire system

why?

(Deceptively) Simple, easy solution

Clean start with the new system

why not?

Downtime for the entire system during the period of switch-over

Unexpected behavior in the new system, from a user’s perspective

State stored in the old system that might be lost

Not transparent to the user

further questions:

- How would we use replication for this?

Replication is not needed/used in this type of upgrade.

- Almost like cold passive replication, but without checkpoints

“Passive replication” involves a primary server that handles all requests and updates the replicas only after processing.

“Cold” implies that replicas are not actively engaged in processing and do not maintain a continuous synchronized state with the primary.

The mention of “without checkpoints” suggests that during the Big Bang upgrade, the state of the system is not periodically saved, which could be risky.

- What’s the downside?

Long downtime

- What about consistency?

The servers will start consistently.

- What about availability?

Availability could be compromised during a Big Bang upgrade because the system might need to be taken offline entirely.

3.3.2 Incremental Replacement

why?

Only specific components might need to be upgraded

Gives a chance to test each component live before wholesale system replacement

Potentially transparent to the user, if done right

why not?

System dependencies might make single-component replacement infeasible

Downtime for the replaced component at a minimum

further questions:

- How would we use replication for this?

Replication is used in a piecewise way, to ensure no downtime for the component being upgraded.

- Almost like warm passive replication with different states and checkpoints

components replacement quicker than big bang, and safer with checkpoints

- Waves of checkpoints

creating checkpoints at various stages

- Intentionally different checkpoints

checkpoints are purposefully different, providing flexibility in handling various issues

- What’s the downside?

It may not be feasible in systems where one cannot isolate the component to be upgraded.

- What about consistency?

Maintaining consistency across the system is a challenge with incremental replacement. As different nodes may be at different upgrade stages, ensuring that they all behave as if they were the same version can be complex.

- What about availability?

Incremental replacement aims to improve availability compared to the Big Bang approach because the entire system does not need to be taken offline at once. However, there may still be periods where certain parts of the system are unavailable or not fully functional as they are being upgraded.

3.3.3 Shadow Operation

why?

Potentially no downtime

Chance to test the entire new system live before committing to it

Transparent to the user, if done right

why not?

Twice the resources, if not more

More bandwidth costs

How long do you keep comparing the two systems?

further questions:

- How would we use replication for this?

You need to replicate every component of the system. Essentially, there are two full systems running in parallel.

- Almost like active replication with different synchronization

Each replica processes requests and maintains its own state.

“Different synchronization” implies that the shadow replicas may be synchronized differently from the primary system to account for the new changes being tested.

Messages go to every “replica” in totally-ordered reliable multicast

- What’s the downside?

Include overhead from maintaining additional replicas and the complexity of managing synchronization across all nodes, especially when different synchronization mechanisms are used.

- What about consistency?

Chanllenging. The system must ensure that the shadow operations do not negatively impact the live operations and that the state of the system remains consistent.

- What about availability?

High availability, by allowing the live system to continue operating normally while changes are being tested on the shadow replicas.

3.3.4 Wrappers

A wrapper is essentially a layer of abstraction that encapsulates the functionality of a component, allowing changes to be made without altering the component directly. This can be particularly useful for adding new features, fixing bugs, or enhancing the performance of the system.

Often used in a way that is decoupled from the main business logic.

why?

No way to capture the old component’s functionality in a way that a new component can be developed

No time/luxury to develop a wholesale new counterpart for each old component

Transparent to the user, if done right

why not?

Could end up being a series of band-aids for each component over time

Underlying problem might still exist—old components not really replaced

further questions:

- How would we use replication for this?

Wrappers could be software modules that encapsulate certain functionalities or changes, which are then replicated across the system.

Messages go to every “replica” in totally-ordered reliable multicast

Replicas are upgraded atomically

- What’s the downside?

Potential downside is the overhead involved in wrapping and unwrapping the functionalities or changes.

- What about consistency?

The system must ensure that all replicas process the same sequence of changes and that the wrappers do not introduce any inconsistency.

- What about availability?

Potentially allow for upgrades and changes to be made with minimal downtime, as they can be prepared and tested in advance before being atomically applied.

3.4 Failure Diagnosis

Collect Data -> Identify Normal -> Detect Deviationsa (From Normal) -> Diagnose Root-cause -> Attempt Recovery

3.4.0 Black-box telemetry

Black-box metrics: OS metrics (CPU utilization, memory usage and ops/sec, disk usage and ops/sec, swap usage and ops/sec, network usage e.g., packets/sec and bytes/sec)

Available on every kind of system

Cheaply collected (relative to white-box)

Coarse-grained: Difficult to diagnose

Non-invasive on the application

3.4.1 Gray-box telemetry

E.g. Middleware metrics, thread-pool size, number of threads used.

has no knowledge of the application

cannot discern problems that are traceable to application-specific behavior

cannot trace application behavior outside of its machine

It is still important because it catches issues that might be in middleware, for example, issues with the Java garbage-collector, with the number of threads, with the number of sockets, etc.

3.4.2 White-box telemetry

Instrument components to emit messages

E.g. Server/Application and System logs

Application-specific, not portable, high overheads

Fine-grained: Highly informative

invasive to the application

does not scale easily as it is specific to each application

3.4.3 How to define Normal

By gathering data to derive signatures of the system behavior under different kinds of workloads, under fault-free conditions.

- Service Level Objective (SLO)

Typically provided by client or dictated by business requirements

Percentile-based SLOs

E.g., 99% of requests completed in < 100ms

- Correctness or Crash faults

User-complaints about wrong service provided

Performance problems: “Fail-slow faults”

- Service Level Agreement (SLA)

Promises made to customers

3.4.4 Detect Abnormal

Path-based Methods

• Clustering of components

• Cluster requests by components reached

• Find components correlated with failures

• Looking for anomalous paths

• Looking for anomalous components on these paths

• What kinds of faults would it catch?

• What kinds of faults would it not catch?

Statistics-based Methods

• Statistical summaries of system metrics

• Metrics: Mean and variance of OS metrics e.g., CPU utilization, memory usage • Use signatures of metrics to identify culprit metrics

• Clusters of metrics

• Build clusters of metric values

• Use clusters as signatures of system performance

• Use signatures to identify anomalous components

• What kinds of faults would it catch?

• What kinds of faults would it not catch?

Log-based Methods

• Statistical summaries of system metrics

• Metrics: Mean and variance of OS metrics e.g., CPU utilization, memory usage

• Use signatures of metrics to identify culprit metrics

• Clusters of metrics

• Build clusters of metric values

• Use clusters as signatures of system performance

• Use signatures to identify anomalous components

• What kinds of faults would it catch?

• What kinds of faults would it not catch?

• This is what Facebook does as well

Visualization

• For large-scale systems, e.g., data centers, long-lived jobs