Cryptography | RSA, DH, ECC

0. Related Knowledge

Detailed info please refer to the mindmap attached at the end of this post.

0.1 Definitions

$y|x$, means x % y = 0, x is evenly divisible by y.

$gcd(a, b)$ represents the GCD(Greatest Common Divisor) of a and b; when $gcd(a, b) = 1$, a and b are Relatively Prime.

- Modular Arithmetic a = b mod m, means $(a - b) \% m = 0$

equals $m \;| \;(a - b)$

equals $b = a \;mod \;m$

$Z_n$, set of integers mod n, E.g. $Z_8$ = { 0, 1, 2, … , 7 }

- $Z^*_n$, set of integers in $Z_n$ that are relatively prime to n, E.g. $Z^*_8$ = {1, 3, 5, 7}

0.2 Algorithms

Euclid’s Algorithm

Goal: finding the $gcd(a, b)$

Claim: $gcd(a, b) = gcd(b, r)$

Process:

\[a = q_1 * b + r_1\] \[b = q_2 * r_1 + r_2\] \[r_1 = q_3 * r_2 + r_3\] \[...\] \[r_n = q_{n+2} * r_{n+1} + 0\] \[(r_{n+1} = gcd(a, b))\]Extended Euclid’s Algorithm

Process:

\[r_1 = a - q_1 * b\] \[r_2 = b - 1_2 * r_1 = (-q_2) * a + (q_1 * q_2 + 1) * b\] \[...\] \[r_i = (...) * a + (...) * b\]Bezout’s Theorem

According to Extended Euclid’s Algorithm, there exist $\alpha, \beta$ such that $gcd(a, b) = \alpha * a + \beta * b$.

When $a, b$ are relatively prime,

\[gcd(a, b) = 1\] \[1 = \alpha * a + \beta * b\]and,

\[\beta * b = 1 \; mod \; a\]Similarly,

\[\alpha * a = 1 \; mod \; b.\]Defines $\beta$ is the inverse of $b \; mod \; a$, and $\alpha$ is the inverse of $a \; mod \; b$.

Euler’s Totient Function

Definition: Euler’s totient function $φ(n)$ is the number of positive integers that are relatively prime to n and less than n. E.g. $φ(8) = 4 = |Z^*_8|$

Facts:

$p$ is prime, $φ(p) = p - 1$.

$p, q$ are distinct primes, Then $Z_{pq}$ = {0, 1, 2, … , (p * q - 1)}, $|Z_{pq}| = p * q$, $φ(n) = (p-1) * (q-1)$

Euler’s Theorem

For all $a \in Z^*_n$, $\; a^{φ(n)} = 1 \; mod \; n$;

That is to say, $a^{φ(n)}$ mod n will be another coprime of n, which is also in $Z^*_n$

For all $a \in Z^*_n$, and $k >= 0$, $\; a^{k * φ(n) + 1} = a \; mod \; n$;

Generalization of Euler’s Theorem

If $p,q$ are distinct primes, $n = p * q$,

for all $a \in Z_n$, $\; a^{φ(n)} = 1 \; mod \; n$;

for all $a \in Z_n$, and $k >= 0$, $\; a^{k * φ(n) + 1} = a \; mod \; n$;

Typically, $a$ represents the message exchanged and $a != 0$ (0 means no information). The first formula ensures that the encrypt-decrypt works. The second formula explains how we could use this theorum to encrypt-decrypt.

1. RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) Cryptosystem

1.1 Intro

Goal

Given the encrypt and decrypt key pair $e$ and $d$ and a message $m$, we could use exponentiation operation to encrypt and decrypt.

\[m^{ed} = m \;mod \;N\]In this formula, $m$ is the message exchanged, $e$ stands for the encryption key, and $d$ represents the decryption key.

Protocol

Between the communication of A and B, defines A as the server who holds a public key $e$ (for encryption) and a secret key $d$ (for decryption).

The client B could use A’s public key to encrypt a message, then send it to A. A is supposed to be able to decrypt it and is the only one who could decrypt it.

Application: encrypt-decrypt, signature.

The security is related with the selection of $e$ and $d$. (Methods adopted to select secure $e$ and $d$ is discussed in 1.2)

1.2 Implement

Method of Key Generation

How to generate a secure $e$-$d$ pair?

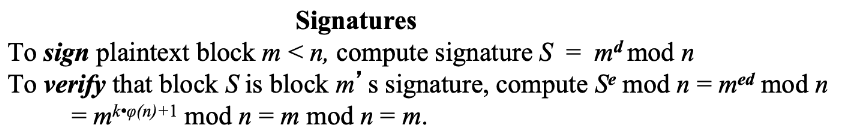

pick a co-prime $p$ and $q$, then calculate $N = p * q$ and $𝝋(n) = (p-1) * (q-1)$;

pick a prime $e$ which is a co-prime of 𝝋(n);

use extended-Euclid to calculate the inverse of $e$ which is the $d$, to make $e * d = 1 \;mod \;𝝋(n)$.

By Extended Euclid’s, $gcd(e, 𝝋(n)) = 1 = e * x + 𝝋(n) * y$, where $x$ and $y$ is unknown, $x$ is the inverse of e (so obviously, $x$ is the $d$ we want).

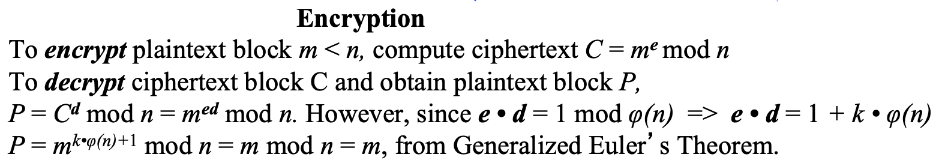

Application: Encrypiton & Decryption

$e, d$ is picked satisfying $e * d = 1 \;mod \;𝝋(n)$. And $gcd(e, 𝝋(n)) = 1 = e * d + 𝝋(n) * k$, so e * d$$

Application: Signature

1.3 Hardness Conjecture

When n is too large, it is computationally hard to find prime factorization $p$ and $q$.

1.4 Vulneralbility & Attacks

Vulneralbility

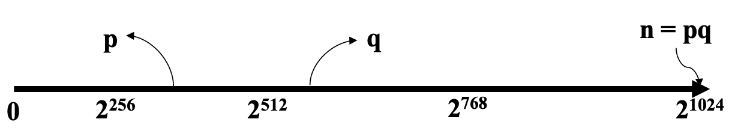

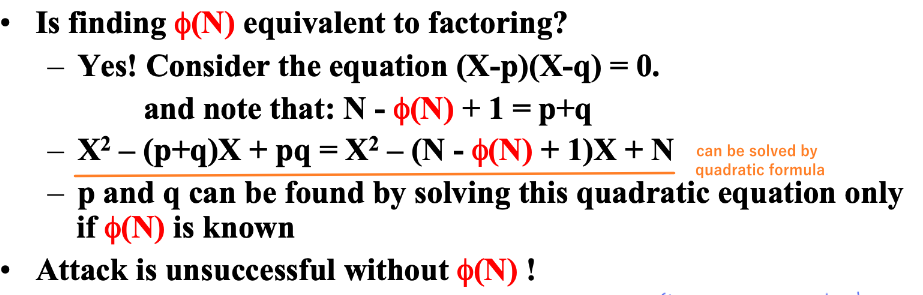

For adversary, knowing $𝝋(n)$ equals to factoring. If the adversary could find $𝝋(n)$, then he can computer secret value d by finding $p$ and $q$.

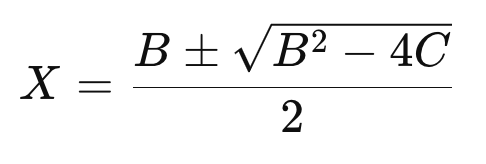

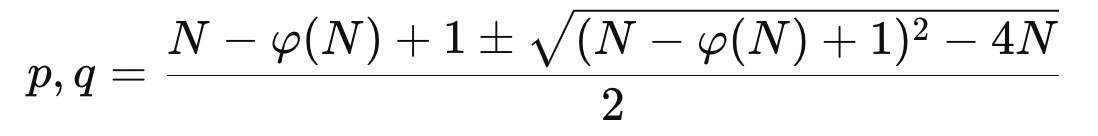

quadratic formula

solution

$𝝋(N)$ is known, but $N$ is still unknown. Why it can be solved? [To be checked]

Attacks

Short-Plaintext Attacks

When encrypting a short plaintext with a small public key, the N might not reduce the result. And it is possible to compute the result by brute force.

Given ciphertext $C$ (with a small length $L$), compute a $C/x^e \; mod \; n$ and a $y^e \; mod \; n$, where $x$ and $y$ is in $(0, 2^{L/2})$. Then if $C/x^e \; mod \; n = y^e \; mod \; n$, $C = (x * y)^e$ and origin message $M = x * y$.

It works when M has two facors each $ < 2^{L/2}$. (So it might be the reason why we need to choose co-prime pairs lol.) It is more easy for adversary to find $\sqrt{M}$ than $M$.

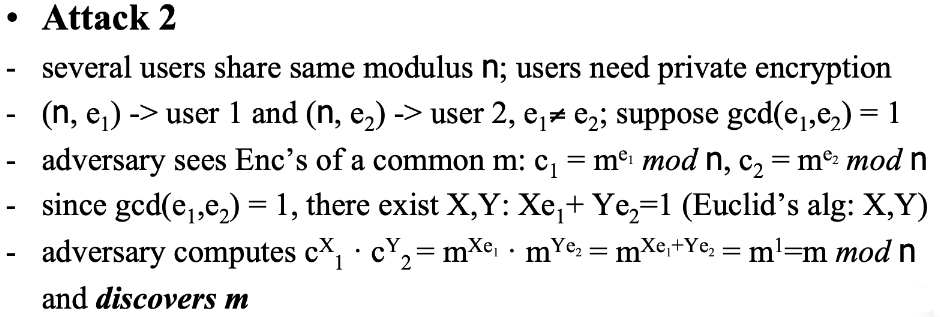

Common-Modulus Attacks

Attack1

Different users share the same modulus n and have different private $e-d$ pairs, then one user i could compute $e_i * d_i = 1 \; mod \; 𝝋(n)$ by:

\[(e_i * d_i -1)/ k = 𝝋(n),\]when d is large, and given d < $𝝋(n)$, so $𝝋(n)$ is also big, then in the formula above, the $k$ must be small. User i could try many small $k$ to get $𝝋(n)$.

If $𝝋(n)$ is known, the user i could find candidate values of $p$ and $q$ by solving $(X-p)(X-q) = 0$. Then verify a possible p-q pair satisfying $N = p * q$ and $|Z^*_N|$ = $𝝋(n)$.

When d is small, see Wiener’s attack (not covered here).

Lesson: decryption key should neither be too big or small.

Attack2

keywords: adversary got common message encrypted with co-prime encryption keys; Extended Euclid’s algo

CCA Attacks

Obtain a ciphertext $c$, create forgery $c’ = r^e * c \; mod \; n$; send to oracle to decrypt and get $m’$; get $m = m’ * r^{-1} \; mod \; n$.

Proof:

\[m' * r^{-1} = (c')^d * r ^{-1} = (r^e * m^e)^d * r^{-1} = r^{ed} * m^{ed} * r^{-1} = r * m * r^{-1} = m \;mod \;n\]if set $r$ = 2, then $m’ = 2m$, (small is good to prevent overflow)

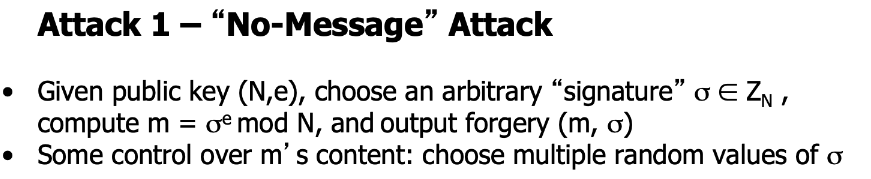

Attacks Against Textbook RSA Signatures

Attack1: No-Message Attack

Randomly choose $\sigma$ and make $\sigma^e = m$ succeed.

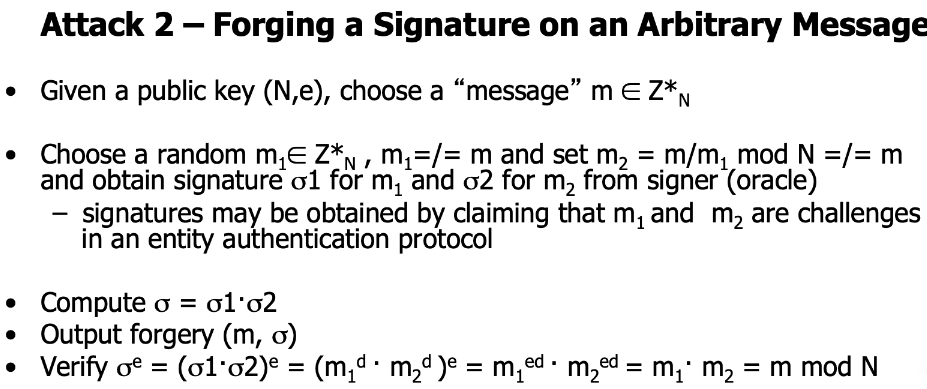

Attack2: Forging a signature existed by arbitrary message

Choosing a pair that when they are encrypted, they could construct the origin encrypted message m.

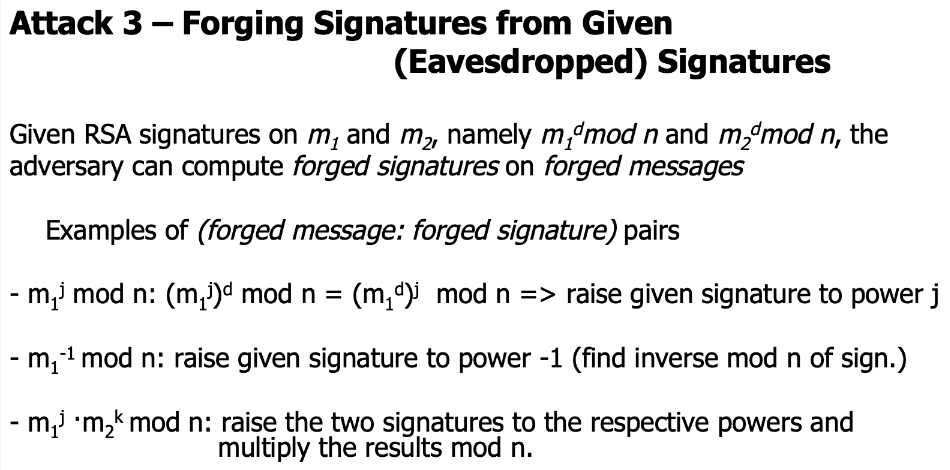

Attack3: Forging signature that could be verified from given eavesdropped signatures

When given signatures, the adversary could forge the signature into another one that could be esier to forge.

Textbook RSA is homomorphic under modular multiplication, which means given $Enc_K(x)$ and $Enc_K(y)$, we could obtain $Enc_K(x \; op \; y)$ for some oprations “op”. The adversary could also exploit this vulneralbility.

1.5 Modes of Encyption for RSA

Protect RSA from attacks.

RSA PKCS #1 & #2

[Skipped]

set some verification bits.

Hash RSA

Generation: $\sigma = [H(m)]^d \; mod \; N$, where H() is a collision-resistant compressing function.

Verification: $\sigma^e = H(m) \; mod \; N$

Can counter the previous mentioned attacks (no message attack, … ), because H() is not revertible.

2. DH (Diffie-Hellman) Key Exchanges

2.1 Intro

Goal

Save the steps for users to efficiently establish secret key.

Protocol

Given a public key $g$. Define A and B each has a private key $a$ and $b$. Then A and B could send a new key to the other:

A -> B: $g^a$

B -> A: $g^b$

Then on each side, they multifplied the key they got to their own private key power. So they shared the same secret at the end. (For A: $ g^{ba} $; for B: $ g^{ab} $)

Note: the $ g^{ba} $ is not used for direct message encrypt or decrypt. It is used for generating other symmetric keys later for encryption and decryption.

Vulneralbility

- Key Exchange without Authentication. Cannot detect man-in-the-middle.

Solution: using authentication portocal.

- DoS attack caused by forced exponentiation; timing attack.

Adversary sending arbitrary messages, looks like the exchanging expotiention key, to B. Then on B side, he must spend lots of time to compute his expotiention. So, he can’t respond to other server’s messages.

Solution: Cypto cookie - MAC. If the message B received does not contain MAC messages, B will not respond to it.

2.2 Secure Level

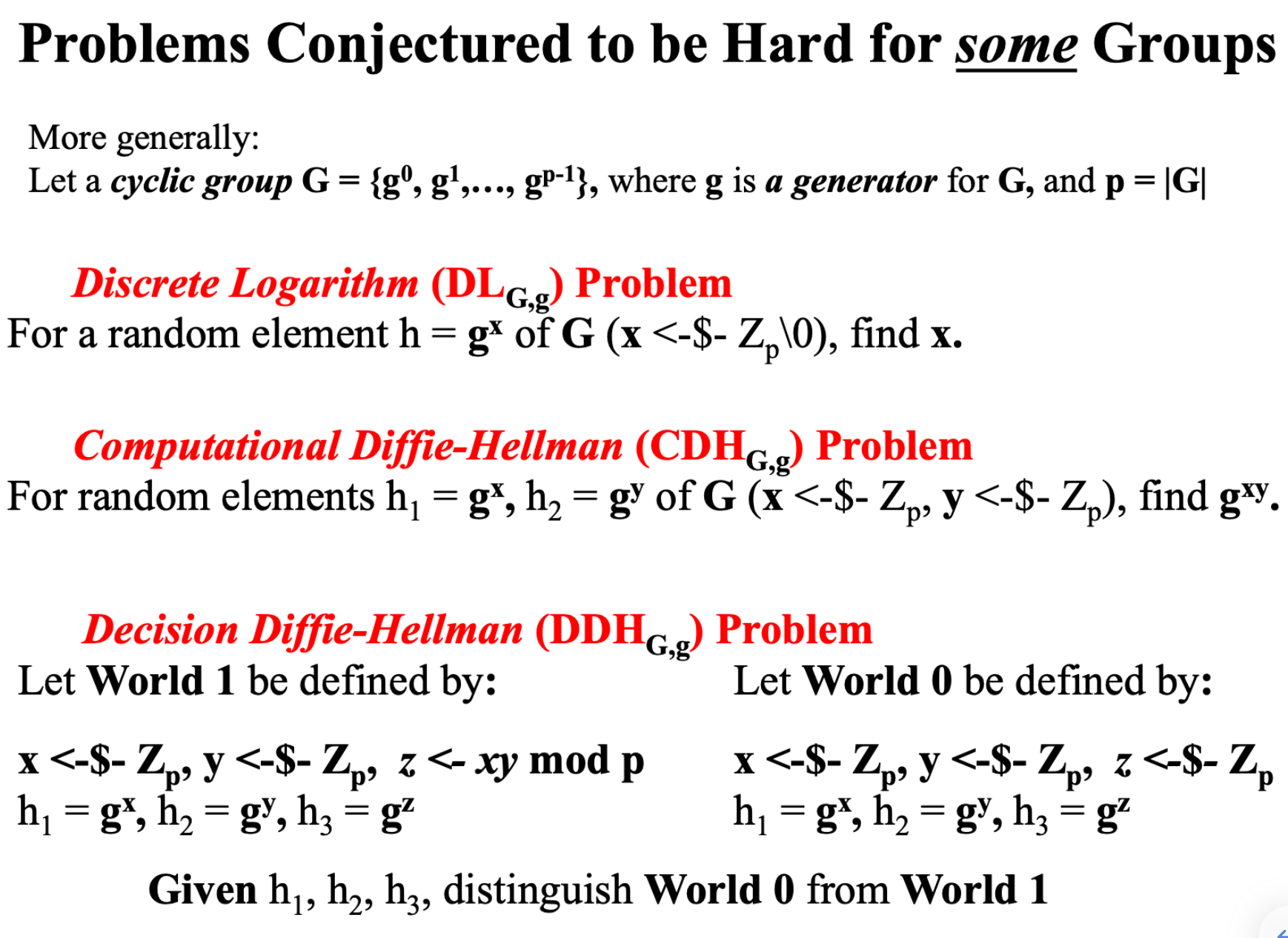

Harder: DDH > CDH > DL

DL is hard in $G = Z^*_p$, $p$ =prime.

2.3 DDH Hard Solution

Goal

Find a subgroup of $Z^*_p$, make the DDH hard.

Solution

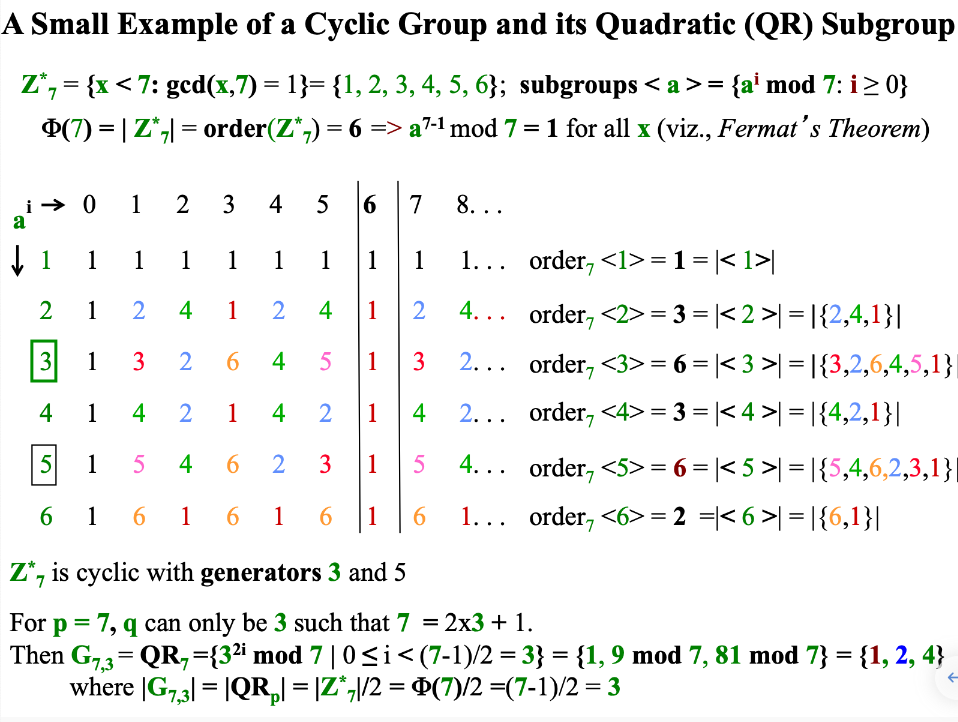

Provide a Prime $q$ and a strong Prime $p = (2q + 1)$.

Define that we have a $G_{p,q} $, a subgroup of $Z^*_p$:

\[G_{p,q} = \{x^2 \; mod \; p \; | \; x ∈ Z^*_p\}.\]It has a property:

\[|G_{p,q}| = q\]The $p$, $q$ and $G$ has some special properties which could ensure the security of the cryptosystem.

$x^2$ generates the entire group $G_{p,q}$, so we could say $x^2$ is a generator of $G_{p,q}$. Similar, $x$ is the generator of $Z^*_p$.

Another subgroup:

By iterating $a$ from $1$ to $q-1$, we could find subgroups candidates $a$, where for $a^i$, $i ∈ [1, q-1]$, every result is distinct. Then we could select a generator $g$ from $a$ to cauculate a new subgroup:

\[G_{p,q} = \{g^{2i} \; mod \; p \; | \; i ∈ [0, (p-1)/2)\}\]

and

\[|G_{p,q}| = q.\]The subgroup $G$ serves as the public key.

P.S. And it has to satisfy that when it was perfromed exponentiation by another number in $G$, the result should exist in the $G$. It is harder for the adversary to find out the generator (public key) used in cryptosystem. Because he found the exponentiation of many generators might lead to the same result. So, the DDH hard is satisfied.

Example

In this case, p = 7, q = 3, $G_{p,q}$ is a subgroup of $Z_p^*$, $|G_{p,q}|$ = q = 3.

3. Elliptic Curve Cryptosystem

3.1 Intro

Elliptic Curve cryptosystem is a more efficient cryptosystem based on the mathematical properties of elliptic curves.

Elliptic Curve family:

\[E = \{(x, y): y^2 = x^3 + ax + b\} \cup \{\sigma\}\]$\sigma$ is the “point at infinity”

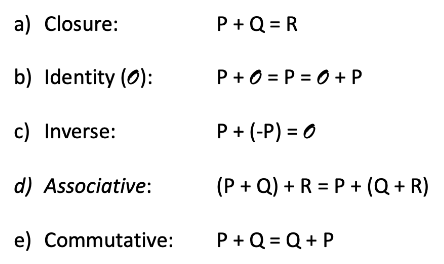

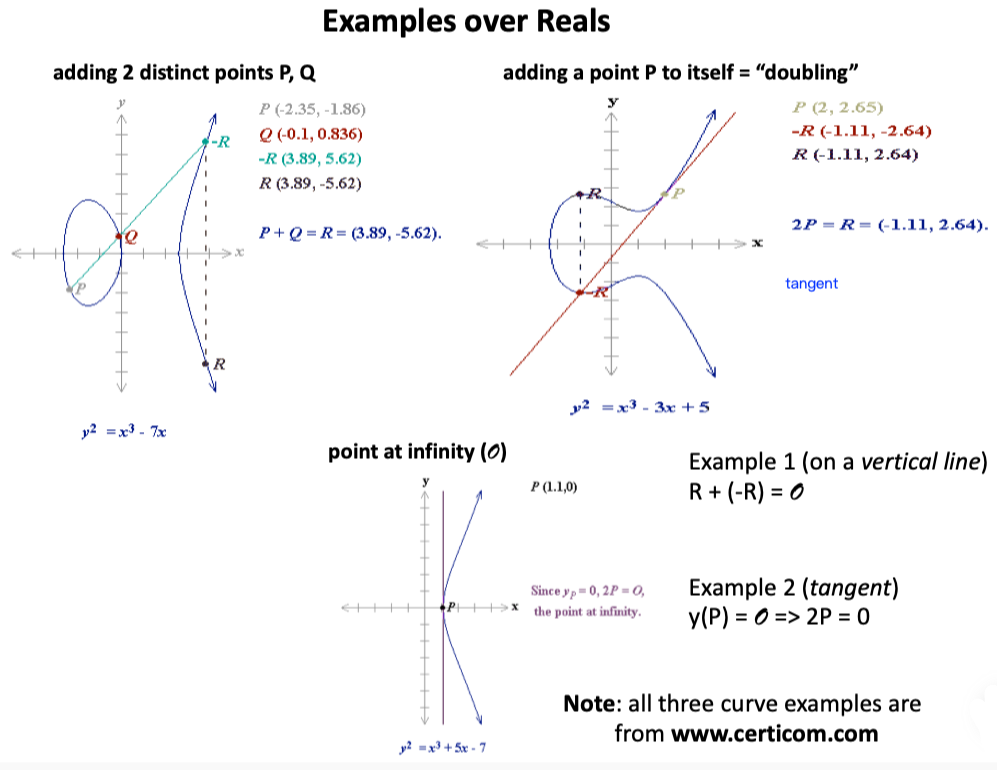

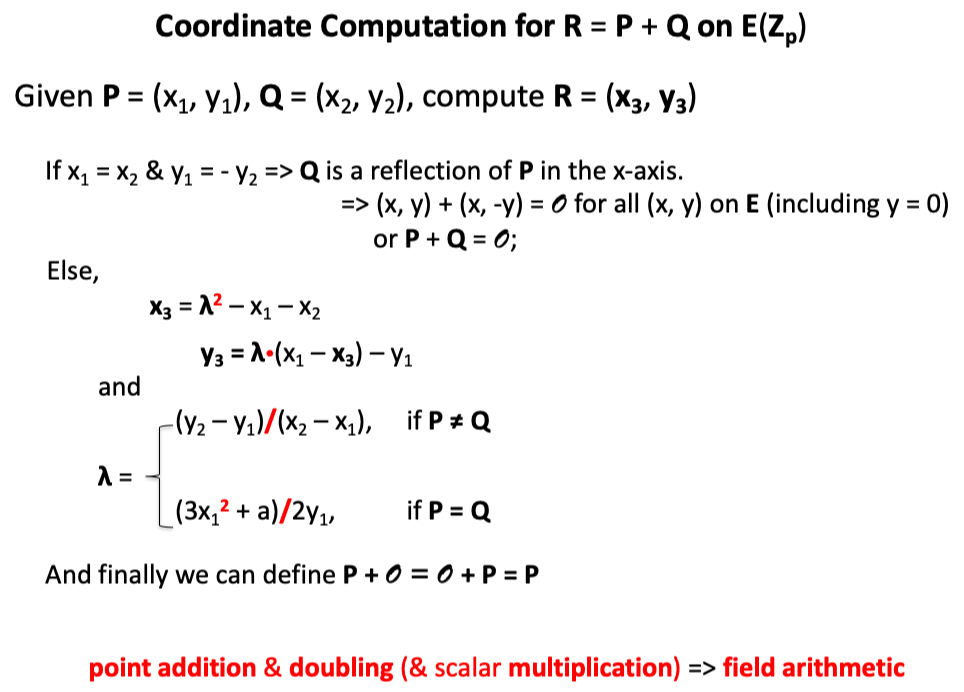

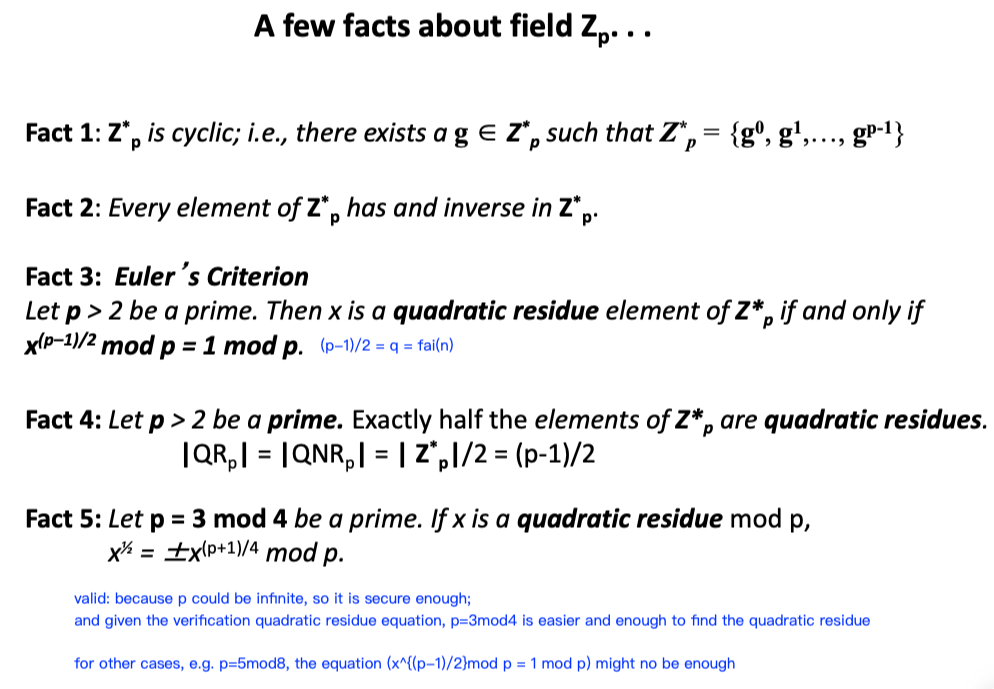

3.2 EC Arithmetic

Given P and Q (points on the curve),

Define $P + Q = R$: $Line_{PQ}$ intersects with curve on another point -R, reflecting -R in the x-axis we got R.

What’s more, $P + P$ means the tangent of $P$ on the curve.

Graphic meaning

Compute Function

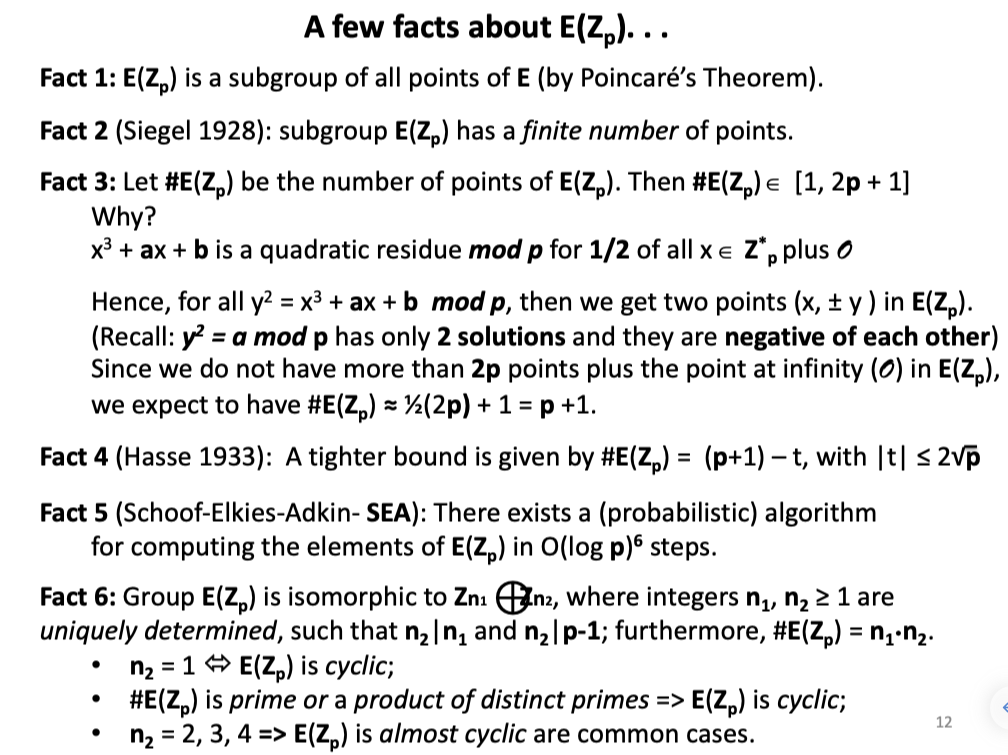

3.3 Properties

✧ Primility Tests

We could never prove for sure if a number is prime, but the following methods provide ways to test if a number is probably a prime.

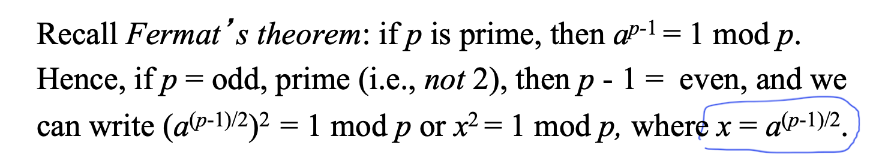

Fermat’s Theorem

Fact

If $p$ is prime, and $a \in (0, p)$,

\[a^{p-1} => 1 \; mod \; p.\]The arrow could not reverse.

Extension

If $p$ = odd prime, then $x^2 = 1 \;mod \;p$, where $x = a^{(p-1)/2}$, derived from:

and $x$ has only two solutions, namely $x = 1$ and $x = -1$.

Miller-Rabin Test

Fact

Given $c$ is odd, $b$ != 0, and a prime $p$,

\[p - 1 = c * 2^b.\]prime $p$ is always an odd number, then $p - 1$ is an even number.

P.S. cases when c is even could be represent by $1 * 2^b$, and by defining the c is odd, it could increase the computing speed.

Implement

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

let b > 0 and c odd > 0 such that n − 1 = 2^b * c # by factoring out powers of 2 from n−1

repeat k times:

a ← random(2, n − 2) # n is always a probable prime to base 1 and n−1

x ← a^c mod n

repeat b times:

y ← x^2 mod n

if y = 1 and x ≠ 1 and x ≠ n − 1 then # nontrivial square root of 1 modulo n

return “composite”

x ← y

if y ≠ 1 then

return “composite”

return “probably prime”

# source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miller%E2%80%93Rabin_primality_test

✧ Related Math Details

Download for best reading experience.

✩ Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Xialin for sharing her class notes with me, and to ChatGPT for clearing my understanding.